Field of Objects: The Preservation of the Domestic Condition

Unpublished.

Thesis supervisor: Antoine Picon

Summary:

My Master thesis at Harvard GSD investigates the contemporary condition of French modernist housing ensembles to examine the relationship between the inhabitants, their objects, and their dwellings. The controversial point at stake is the way in which these projects, the so-called grands ensembles, are occupied nowadays.

Found in the banlieues on the perimeter of Paris, grands ensembles represented the post-WWII implementation of the Rationalist urban dream. However, the visionary blank space of Corbuisian minimalism, once the bearer of a new idea of living, has today lost its revolutionary purpose, representing now conflict between planning and cultural memory.

I first intend to clarify the thesis' very title: “Field of Objects” by introducing the peculiar approach or methodology I applied to my research, I will then summarize the historical background and I’ll finally tackle the key concepts that emerged from my research.

In this regard, I was very influenced by the properly Italian attitude towards design, “from the spoon to the town,” that not only recalls the famous Aldo Rossi’s coffee pot “La Cupola,” but relates also to what Leon Battista Alberti wrote “[t]he city is like a big house and the house in turn, a small city.” This opened up a peculiar scale-less approach to design that became instrumental for the formulation of my thesis. I therefore uncovered the cultural dimension of domestic interiors for a provocative reformulation of the concept of heritage that includes the banality of everyday life. My analysis was possible thanks to the proposed blurred limit between objects, furniture, architecture and the city that introduced me to the imaginary landscape of the interiors in which objects and monumental pieces of furniture are seen as true fragments of cultural heritage.

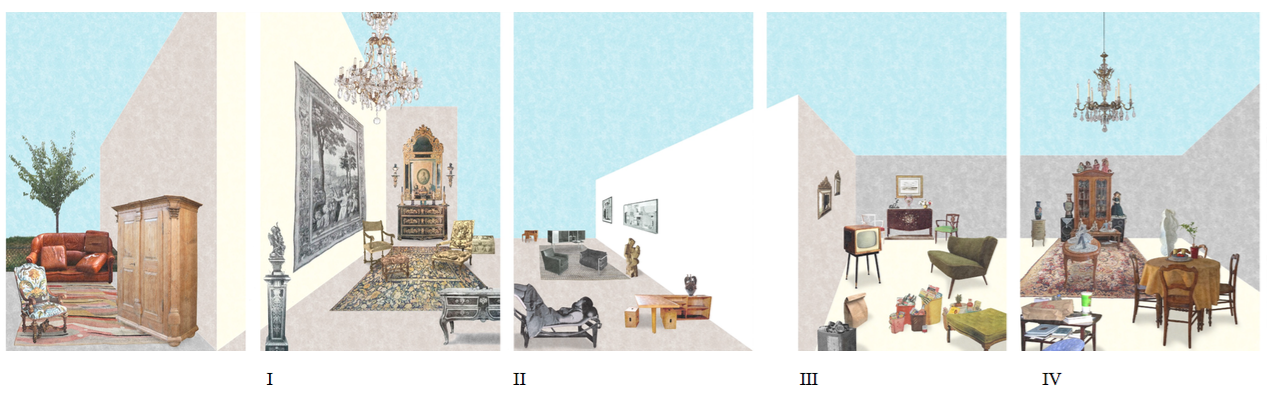

A series of paintings by the metaphysical artist Giorgio de Chirico exemplifies these concepts. Pieces of furniture, displaced from their architectural framework, condensed his hidden desire to recreate a never achieved sense of domesticity through the grouping of the fragmentary nature of his memories, encapsulated in the series Mobili nella Valle (Furniture in the Valley). Once decontextualized and displayed in a landscape setting, the isolated pieces expose the intimacy of domesticity, the personal time dimension of interiors, the woven network of affections and memories that occupy the space of the house. The series synthetizes all the scales of inquiry that characterize my research: the potentially endless landscape of domestic interiors hosts from the smallest fragment, both real and imaginary, to the larger scale of freestanding containers, such as drawers or architecture, up to built and unbuilt fields. All of this is what I called the all-encompassing “field of objects.”

My thesis, as exemplified in these illustrations, doesn’t follow a continuous narrative. Although each chapter is arranged chronologically, each of them has to be seen as an isolated entity, that can or can’t relate to the others. This is connected to the peculiar time dimension of domestic interiors: instead of proceeding on a historical timeline, it remains steady or, rather, replicates itself within the tradition and permanence of a certain social structure.

The focus has been on the French bourgeois apartment because of the tight connection of the social group with economic capital, accumulation and later with consumption, which highly influenced dwelling habits, taste and the process of definition of the class’ identity. However, if on the one hand the economy moves quickly, on the other hand the slow consolidation of a self-identification through consumption generates a stasis, which is manifested, not by chance, in the realm of interiors.

During the 19th century, French architects and treaties writers on “Private Architecture,” focused on the so-called science of the savoir-vivre (“good living” or “knowledge of life”) where the urban upper and middle-class were described as the norm, establishing the dwelling program and its spatial organization (as shown in these diagrams). Through the art of distribution, the dwelling typology was defined according to the new principles of “good living” and the architect assigned to each inhabitant his own place in the same way the individual elements of furniture qualified the function of the rooms.

The internal distribution resulted in an ideological spatial division within domestic walls between the masculine (public space) and the feminine private half, proving that architecture could enable the clear understanding of the distribution of both roles and power within the socially constructed reality of the family. Interestingly, the spaces for public reception were often tripartite: the center was occupied by the large living room (the salon) and the two sides hosted the two bedrooms of the husband and wife. Both chambers opened to the salon so all three combined environments had the function of representing the family wealth and status.

In 1800s France, mass production was embedded in the economy and certain goods such as pieces of furniture or domestic items, by virtue of their major accessibility, immediately lost that character that once defined the authentic product of tradition. As a matter of fact, inside their convoluted interiors, the newly enriched bourgeoisie imitated the taste and lifestyle of the old aristocracy, following an elusive ideal of luxury that was consequently imitated by the lower and middle-classes. The modest dwellings, then, became populated by new, accessible, industrially produced pieces of furniture, harshly criticized by the wealthier as they recreated a faux luxe (false luxury). Thus, the meanings that were attributed to objects certainly reflected aspirations to social mobility, embodying a hidden desire to possess items which were symbols of wealth. Interior decoration was therefore sought by all social classes.

In the meantime, as life became less formal, a new idea of being chez-soi (at home) gradually began to emerge. The result were impressive changes as lower and middle-class members began to marry for love and share the same bed inside the new “parents’ room,” which will become the norm from the second half of the 19th century onwards. Through my research I discovered that the Henri Bracque type, an early 20th-century layout, became the model for French public housing and society during the second half of the 20th century. In fact, after the 2nd World War, France undertook a gradual process of modernization and reconstruction that allowed the so-called Technocratic Modernism to serve the municipal administrations to manage the French territory. They implemented their total planning through the massive realization of the grands ensembles. They were placed in the outskirts of many French cities and were targeted to the middle-class citizens, aiming to host the nuclear family: founding element of the social reform of a post-war nation.

As could be expected, government planning led to standardization in specific apartment types: F4 represented the dull repetitiveness of normalized, banalized domesticity, housing the "model family." The new ideal modern lifestyle was presented in contemporary magazines, but also in new television and so on. So the dwelling soon became main domain of consumption, which resulted in the so-called “cult of objects” fostered by the new medias. The interior of the house became once again a space for the accumulation of things, strongly desired by French young couples, whose dreams were partially fulfilled in the newly built ensembles. There, the habit of carefully curating interior domestic representational spaces remained part and parcel of the household preoccupations.

____

Technocratic Modernism, however, highly differenciated from the violent reaction to ornament that, on the other hand, characterized the 20th-century reaction of Modernist openness and flexibility as opposed to the conservative bourgeois closing and fixity. Le Corbusier, among many, distinguished himself for the active engagement in designing a new habitat, instrumental for the production of a new, modern subject. The architect, through the collection of folk artifacts and heterogeneous objects - and later on, through the design of pieces of furniture – focused large part of his career on interiors. His personal collection particulière (particular collection) followed him in both his Parisian residences, whose interior arrangement largely differentiated from the architect’s theoretical and architectural production of the time.

Remarkably, in 1935 Le Corbusier hosted in his house the exhibition “The so-called Primitive Arts in Today’s Home” where he displayed his own collection together with contemporary cultural objects and industrial types. An interesting temporal juxtaposition of ancient artifacts and mass-produced objects reminds us of his recurrent, personal methodology of selection, decontextualization and recontextualization of images and types. We can thus say that the architect’s almost curatorial practice of disposition, or juxtaposition of contemporary and historical artifacts, is an important moment of the appropriation of interior spaces of the house because it exemplifies the practice of representation of the modern subject’s identity.

If we think of Le Corbusier’s later production as a mature synthesis of his former education as decorator, it is possible to look at both his paintings and interior arrangements as products of the same careful selection of a grammar of basic types, the so-called objet-types. This limited alphabet was a set of isolated objects, generic items of domesticity found in common life that were able to generate poetry in Le Corbusier’s architectural still lives, displayed, inter alia, in his Esprit Nouveau Pavilion. In fact, we can look at it as an object and container of other smaller objects (furniture, paintings and so on), basically a large matryoshka of exhibition props.

So, following both the semantic reading of Corbusier’s work by architectural historian Renato De Fusco, professor Alina Payne and Gaston Bachelard’s philosophy of imagination, we can say that by means of “decoration” and by virtue of encasing objects and everyday life, furniture can be considered as architecture in miniature, while architecture can encompass the qualities of gigantic pieces of furniture. This opens up the vastness of the miniature world or greatly reduces the fields upon which objects (at all scales) are placed.For instance, the mechanical eye of the periscope placed on top of Beistegui Penthouse was able to capture the architectural landmarks of Paris, standing out from the homogenous field of the city fabric. On top of the same penthouse, a free plan opened the space of a room under the sky. The compositional syntax of the renowned “baroque furniture” and the presence of “real grass” creates a truly interior landscape, a real field of objects. The presence of isolated entities within the space connects at multiple scales, once again, the much subtler and poetic expedient of a carefully curated disposition of objects. Indeed, while describing his own, personal interior landscape, Le Corbusier writes: “I live in my archipelago, my sea, it’s thirty years of accumulations diversely attached to intellectual and manual activities. Here and there, on the ground, groups of objects, devices, books, texts, drawings. These are my islands!” Only now, the subtle power and the multiplicity of meanings of all the seemingly irrelevant everyday life objects start to emerge. This landscaped view of the interior immediately recalls De Chirico’s watercolor. Memories, like scattered ruins over the metaphysical landscape, evoke a broader lost temporal dimension.

Ora questo è perduto (Now all of this is lost) is the title of a Rossi’s drawing that exemplifies this concept. His repertoire of broken architectures acts exactly as the furniture of De Chirico’s series of paintings, or Beistegui’s baroque pieces. All three instances refer to lost, incomplete, allegorical meanings that go beyond our understanding. A lesser-known image - a collage made for the Salon d’Automne - reveals an astonishing similarity with the Beistegui photograph. Both central perspectives represent a seemingly homogeneous architectural site with scattered pieces of furniture disposed in an almost identical position. This expedient seems therefore to be the recurrent theme in Le Corbusier’s representation of his interiors, which goes hand in hand with the representation of the modern subjectivity.

Noticeably, the two images differ in furniture style, still perfectly representing a so-called “field of objects.” This is central to my argument, as such stylistic difference is still present in contemporary conditions of living, exemplified by two different modes of inhabiting: the one belonging to traditional families, still fascinated by the old figurative codes of interior furnishings (as it connects back to the fundamental values of the dominant cultural model of the bourgeoisie); and the younger, contemporary families which prefer a modern language. We are tempted to separate the two lifestyles in terms of a generational discrepancy, however, French philosopher Jean Baudrillard gives us the key to understand that the subtle system of power relations goes beyond the aesthetic appearance of the “system of objects” in place. In fact, he explains that despite the contemporary “absence of style” of modern furniture, their symbolic value remains intact, as the simplification of forms does not necessarily convey a final liberation from the expressive power of the symbolic order. In fact, no real emancipation can occur if it is not followed by a complete restructuring of both the domestic space and its social hierarchies. Unfortunately, structural social changes have not been yet absorbed in toto by the broader strata of society because the meanings attributed to goods are fundamental for the definition of identity and culture, oftentimes associated to the certainties of tradition.

As we’ve seen, through the process of industrialization and later to that of mass production and consumption, the meanings attributed to certain forms and decorations maintained the original connection with wealth and luxury that never detached themselves from the theatricality of the voluptuous forms typical of the Baroque. The latter, not by chance, is considered the first moment in time in which – according to art critic and philosopher Gillo Dorfles – “kitsch” appeared. It’s worth pointing out that his definition of “kitsch” is more open than many others. In fact, Umberto Eco - following Dorfles’ definition - pointed out in his book on Ugliness that since the concept of taste is itself very fluid and never purely truthful, to consider “kitsch” as “ugly” is nothing but a purely social construction, controversially opening up to the aesthetic qualities of kitsch. We, therefore, embrace this approach and consider kitsch as our fundamental category of analysis as it manifests mainly in the domestic realm. This happens because its objects’ scope is that of reassuring, protecting, and comforting - since they generally belong to the categories of good feelings, traditional rituals and all that reflects the ordinary family group. So kitsch represents here a cultural category per se, a truthful aesthetic referent.

____

“Never demolish, never remove or replace, always add, transform and re-use!” Is the renowned motto of French architects’ Druot, Lacaton & Vassal “Plus theory” that has been analyzed in order to both situate their architectural contribution in the theory of conservation, and to investigate contemporary dwelling habits inside modernist housing estates. The “Plus principle” consists of a system to refurbish grands ensembles instead of demolishing them, since they are today spaces of decay, confinement and poverty. It aims to expand the interior surface of the dwellings through the addition of a series of prefabricated balconies. With their sensitive approach, the architects de facto deconstruct the historical bias against grands ensembles by recognizing their latent potentialities. In short, preservation here is the act of novelty: not to demolish, in the case of housing (i.e. real estate interests) represents an act of resistance to the conforming forces of the market. If we look at Tour Bois le Prêtre in Paris, we notice that the new architectural addition of Plus generates a threshold, as the new space provided has the quality to expose existing conditions. This image condenses the time dimension of domestic interiors as a receptacle of eclectic fragments that, using Walter Benjamin’s vocabulary, are true “debris of history,” since they represent “commodities for which the status of ‘phantasmagoria’ has decayed”, “sedimenting” in layers of material culture.

In line with the architects, we can say that in this project what is truly, purposefully preserved are exactly those small debris, ruins, leftovers of everyday life. Seen as the remnants of a broken wholeness, in our case an ideal domestic dimension that tried in time to find its space exactly in the pigeonholed structure of grands ensembles. Photographs taken inside the tower show a condition in which outmoded pieces of furniture and decorations today still inhabit the space of the house. The everyday objects and the old-style monumental furniture displayed in the tower, all persist within the domestic space as the unchanging elements of the interiors. The very definition and consolidation of the family structure and its social hierarchies is relentlessly replicated despite the radical changes that the Modernist housing ensembles represented. This condition is registered, respected, accepted and even appreciated, by the architects and that’s why preservation is invoked in the realm of the house.

____

“Now in the little lounge what is left is what remains when there’s nothing left: flies, for instance (...) or those things without meaning that lie around on floors and cupboard corners, you never know how they got there nor why they stayed: three faded flowers of the field; (…) an empty Coke bottle, a cake box, opened …”

George Perec describes in this passage our domestic leftovers. Each one of them is, indeed, a debris, a remnant, a result of consumption, a referent to memories. Those items are the ones that populate the field of objects, symptomatic manifestation of interiority inside domestic interiors. The “lost object,” theorized by philosopher Giorgio Agamben, does not differ from our domestic ruins and broken memories: it satisfies a human desire by virtue of its elusiveness and by being tangible presence of an absence. It is situated in a threshold between the oneiric and the real world, between the self and the external choice of objects, part and parcel of culture. This clearly describes our field of objects, encompassing Ora tutto questo è perduto and Mobili nella Valle. Agamben gives us the last instrument to understand the very title of this thesis, that spans from the realm of subjectivity to that of the cultural landscape of a social group. In this regard, a recent exhibition at the New Museum titled The Keeper exhibited personal collections, presenting itself as the “museum of the individual,” the one advocated by the writer Orhan Pamuk. To him, the house has the qualities and potentialities to preserve those remainders of culture that according to their careful disposition, portray true identity. It is for these reasons that they are worth being kept in their original environment, re-creating universal conditions by showcasing the ordinary. In other words, personal heritage worth being preserved and exhibited as much as cultural heritage, as their true nature lies in their ruined status, their quality of discarded elements from the contemporary pace of life. This is the reason why we can compare the old, monumental pieces of furniture to monuments or architectures, and why insignificant objects of ordinary life can be elevated to the status of cultural artifacts.

What seems to be needed at this point is thus a total reformulation of the same concept of heritage that includes the “everyday.” This simple yet provocative idea has been recently embraced by the ICOMOS during a conference where I had the chance to present my thesis. They, indeed, acknowledged that a new notion of “mobile” heritage should be taken into consideration as a new category.

To conclude, I am not sure whether I do agree on the “Preservation of the Domestic Condition” advocated by Pamuk and the French trio, as such conception is indeed highly disputable. These considerations, however, go beyond the scope of my thesis. This research, instead, wants to highlight a real phenomenon that has been widely neglected, but I consider being quite relevant for architects. In fact, it includes the chaotic yet fascinating reality of everyday life, that patina of dust which inevitably grows within architecture’s walls, as Alois Riegl puts it, “[a]ge-value manifests itself less violently, though more tellingly, in the corrosion of surfaces, in their patina, in the wear and tear of objects” and the same thing happens through the process of inhabitation. Kitsch interiors in Modernist housing inevitably disturb the educated eye of the architect, in fact, Riegl continues “[w]e are disturbed at the sight of decay in newly made artifacts”, decay in our case is manifested by the little ruins, or the permanence of the traditional family structure, the old figurative vocabulary of furniture, and the presence of personal memories inside the architectural epitome of modern times.

© Francesca Romana Forlini